Curious Kids: How come Donald Trump won if Hillary Clinton got more votes?

Sarah Burns, Rochester Institute of Technology

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

How come Donald Trump won if Hillary Clinton got more votes? Ellen T., 8, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Many Americans wonder why Donald Trump became president after the 2016 election, since Hillary Clinton got more votes overall.

In fact, Clinton got as many votes in 2016 as Barack Obama did in 2012. Hers were concentrated in fewer states, however, which makes all the difference in the American political system.

I’m a professor who studies the presidency. To explain why Trump won we have to go back to the founding of the United States.

What is the Electoral College?

In the United States, something called the Electoral College determines how many votes a presidential candidate gets in an election.

Each state has a certain number of votes for presidential candidates roughly tied to the population of the state. This number is equal to the number of representatives and senators the state sends to Congress.

For example, New York, the state where I live, has 27 representatives and therefore 29 Electoral College votes. Washington, D.C. — which doesn’t have any members of Congress — has three Electoral College votes.

But the rules also say each state must have at least one representative and there can only be 435 members of the House. Because of the way those available seats are divided up, certain states have fewer representatives per person than in other states.

For example, each of the 53 representatives in the House from California represents roughly 746,415 people. In Wyoming, that number drops to 577,737 for their one representative.

This means the national popular vote – which goes to the candidate who won the most individual votes – can be somewhat different than the Electoral College vote.

That’s what happened in the 2016 election. Large portions of city-dwellers in blue states voted for Clinton, giving her the most votes nationally.

But Trump had an advantage in states with smaller populations and an advantage in the Electoral College. This is in part because 48 states and the District of Columbia give all of the electoral votes from the state to the candidate who wins the majority of the votes. Only Maine and Nebraska don’t follow this ‘winner takes all’ approach.

Where did it come from?

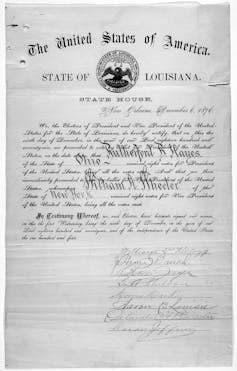

The Electoral College is part of the U.S. Constitution.

In 1787, the Founding Fathers worried that the people might elect a demagogue, or someone who would appeal to their emotions and facilitate the creation and execution of laws based on fear or anger. The founders assumed the electors in the Electoral College would just be “unfaithful” to the voters if they voted for someone unqualified.

In modern times, people in all 50 states vote in November and those decisions are conveyed to the electors. The electors meet in mid-December to cast the official ballot for president.

Almost always, they adhere to the votes of the people, but every so often an unfaithful elector votes for a different candidate. Electors are generally chosen by the party – Republicans and Democrats – but each state determines for itself how it chooses electors.

In the case of the 2016 election, electors largely voted with their states, electing Trump president.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Sarah Burns, Associate Professor of Political Science, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.