SCOTUS could exclude waterways from clean water protections

(Northern Rockies News Service) A coalition of groups focused on water rights filed a brief in June with the U.S. Supreme Court to keep the court from narrowing the definition of federally protected waters.

Waterkeeper Alliance, San Francisco Baykeeper, Bayou City Waterkeeper, and nearly 50 additional Waterkeeper groups from across the country filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in support of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the case Sackett v EPA.

The clean water advocates are asking the Supreme Court to uphold the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling about the scope of wetlands protected under the landmark Clean Water Act.

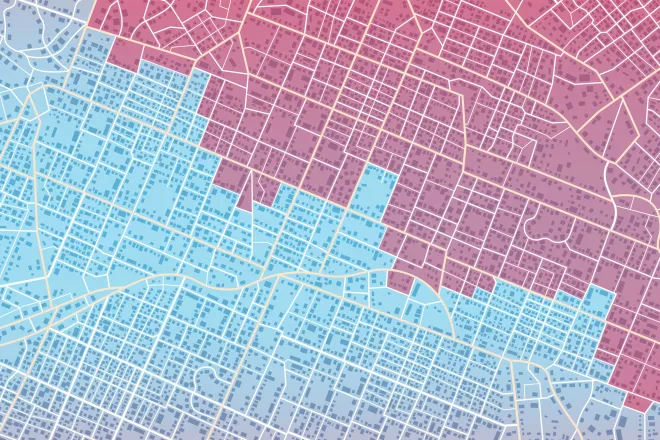

The central question in Sackett v EPA is what standard should apply to determine protection for wetlands that are adjacent to traditional navigable waters and their tributaries. The petitioners in the appeal have asked the Supreme Court to overturn the Ninth Circuit's ruling that adjacent wetlands, including those on their Idaho property, merit federal protection, which would advance a narrow interpretation of the CWA. The amicus brief contends that, to achieve the law's objective, it must protect all waters that make up aquatic ecosystems, not just navigable waters. The Supreme Court will hear the case this fall.

"Idaho has unique geographical and hydrologic features that form 'closed basins' which would be excluded from federal pollution protection if Clean Water Act jurisdiction was reduced by constricting the definition of which 'waters of the United States' are federally protected," said Buck Ryan, executive director of Snake River Waterkeeper, in an interview with The Daily Yonder. "We joined in filing the brief to ensure these waterways - which are critical to water quality in the Snake River as well as for endangered species like bull trout - enjoy the federal statutory protections Congress intended in drafting the Act."

The Clean Water Act was enacted in 1972 to protect the health of the waters of the United States, promote healthy aquatic ecosystems, and regulate the discharge of pollutants into waterways.

In states like Idaho, Ryan said, "where industry and ag-friendly legislatures offer the bare minimum in terms of clean water safeguards, the federal Clean Water Act is the preeminent (and in many cases, only) guarantee of legal protection for rural communities to have fishable, swimmable, and drinkable water."

Kelly Hunter Foster, senior attorney with Waterkeeper Alliance, said many iconic and significant waters across the country lack continuous surface connections to traditionally defined navigable waters and could lose federal clean water protections that have been in place for nearly 50 years if the court were to adopt the petitioners' navigability theories.

"Congress originally designed the CWA to broadly protect all waters of the United States-not only those used for commercial navigation. The scope cannot be narrowed if we are to ensure the integrity of the law and the health of our waterways," Foster said in a press statement.

The Supreme Court's hearing of the challenge to the CWA occurs as the court has revisited long established precedents. Last month the court ruled that the Clean Air Act does not give the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency blanket regulations against power plants. The Clean Air Act, initially passed in 1963 and revised many times since, was one of the nation's first and most influential environmental laws.

Waterkeeper Alliance Chief Executive Officer Marc Yaggi called the court's interpretation of the Clean Air Act a "gift to polluters and will pose a major threat to clean water."

"The majority's new major questions doctrine handcuffs the federal government's ability to respond to emergencies that weren't specifically contemplated at the time statutes are passed," Yaggi said in a press statement. "The idea that our current dysfunctional Congress might be expected to more directly authorize EPA to broadly 'tackle' the climate emergency is absurd. This sets a dangerous precedent not just for EPA and our climate, but for all agencies and future emergencies."

Albert Lin, a law professor at the University of California Davis who specializes in environmental and natural resources law, said in an interview that the Clear Air Act and Clean Water Act cases seem to be asking two different questions. The Clean Air Act case used the major questions doctrine, he said, and he believes it's unlikely that will be the case in the Clean Water Act case.

"It seems unlikely given that the sort of question at issue in the Clean Water Act case, the extent of the government's regulatory authority over wetlands is an issue that the agencies - EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers - have been grappling with for decades," he said. "And that it's not the sort of situation as in West Virginia vs. EPA, where you had, at least the way the court puts it, EPA asserting this apparently new authority over how kind of energy is produced and distributed and generated."

Also in June, the Supreme Court overturned its landmark Roe v. Wade decision of 1973, which provided a constitutional basis protecting the right to abortion services.