Tribal traditional healing gets Medicaid reimbursement in 4 states

Art Martinez has seen the power of ceremony.

Martinez, a clinical psychologist and member of the Chumash Tribe, helped run an American Indian youth ceremonial camp. Held at a sacred tribal site in Northern California, it was designed to help kids’ mental health. He remembers a 14-year-old girl who had been struggling with substance use and was on the brink of hospitalization.

On the first day of the four-day camp, Martinez recalled, she was barely able to speak. In daily ceremonies, she wept. The other kids gathered around her. “You’re not alone. We’re here for you,” they’d say.

© iStock - nevarpp

Traditional tribal healing practices are diverse and vary widely, unique from tribe to tribe. Many include talking circles, sweat lodge ceremonies with special rituals, plant medicine and herb smudging, along with sacred ceremonies known only to the tribe.

Martinez and the girl’s counselor saw her mental health improve under a treatment plan combining tribal traditional healing and Western medicine.

“By the end of the gathering, she had broken through the isolation,” Martinez said. “Before, she would barely shake hands with kids, and she was now hugging them, they were exchanging phone numbers. Her demeanor was better, she was able to articulate.”

Indigenous health advocates have long known the health benefits of integrating their traditional healing practices, and studies have also shown better health outcomes.

Now, for the first time, tribal traditional healing practices are eligible for Medicaid coverage in California and three other states under a new initiative. Last October, the federal government approved Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage of traditional healing practices at tribal health facilities and urban Indian organizations in Arizona, California, New Mexico and Oregon.

These were approved under a federal demonstration provision that allows states to test new pilot health programs and ways to pay for them.

© zimmytws - iStock-2206705589

Arizona’s waiver went into effect Wednesday. While California’s waiver currently only covers patients with substance use disorder, like the girl in Martinez’s camp, any Medicaid enrollee who is American Indian or Alaska Native is eligible in the other three states. Officials have said California’s program will expand to have such coverage in the future.

Under the waivers, each tribe and facility decides which traditional healing services to offer for reimbursement. Services can also take place at sacred sites and not necessarily inside a clinic, explained Virginia Hedrick, executive director of the California Consortium for Urban Indian Health.

“If a healing intervention requires being near a water source — the ocean, creek, river — we can do that,” said Hedrick, who is of the Yurok Tribe and of Karuk descent. “It may involve gathering medicine in a specific place on the land itself.”

Tribes long had to practice out of sight. The U.S. government’s assimilation policies had targeted tribal languages, cultural and religious practices — including healing. It wasn’t until 1978, when the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was enacted under President Jimmy Carter, that they regained their rights.

“It was illegal to practice our ways until 1978 … the year I was born,” said Dr. Allison Kelliher, a family and integrative medicine physician, who is Koyukon Athabascan, Dena. “Traditional healing means intergenerational knowledge that have origins in how our ancestors and people lived generationally to promote health, so it’s a holistic way of looking at well-being.”

Last month, Kelliher and hundreds of others gathered at the National Indian Health Board’s health conference on Gila River Indian Community land in Arizona. During a panel discussion about the waivers, tribal members discussed how health centers will bill for services, ways to protect the sacredness of certain ceremonies, and how to measure and collect data around the effectiveness of the treatments, a federal requirement under the waivers.

© Rebecca J Becker - iStock-1251580456

But teasing out those new protocols didn’t dull the enthusiasm.

“This is where we really start intersecting the Western medicine as well as traditional healing, and it’s exciting,” said panelist Dr. Naomi Young, CEO of the Fort Defiance Indian Hospital Board in Arizona.

The Trump administration announced earlier this year that it doesn’t plan to renew certain other Medicaid waiver programs approved under the Biden administration. But it hasn’t announced any changes around the traditional healing waivers.

Studies have found that Incorporating sweat lodge ceremonies and other cultural practices in treatments led to substance use recovery and emotional health, and better quality diets when incorporating traditional foods, according to analyses of research by the National Council of Urban Indian Health.

“When there is an opportunity to braid traditional healing with Western forms of medicine, it’s very possible, and the research is indicating, we may get better health outcomes,” Hedrick said.

Traditional practices

Decades of historical trauma, such as displacement and forced assimilation in boarding schools — where American Indian and Alaska Native people were forbidden from speaking their languages — are behind their disproportionate rates of chronic illness and early deaths today, tribal health experts say.

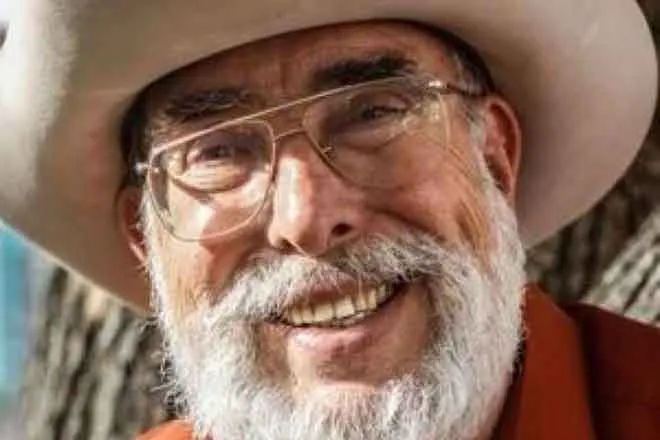

Tribes have long offered traditional healing — both outside brick-and-mortar health care settings as well as within many clinics. But health centers have been paying out of pocket or budgeting for the services, said retired OB-GYN Dr. John Molina, director of the Arizona Advisory Council on Indian Health Care and member of the Pasqua Yaqui and Yavapai Apache Tribes.

Molina said the new Arizona waiver may help clinics afford to serve more patients or staff more traditional healers, and build infrastructure, including sacred spaces and sweat lodges. For other clinics, “They’ve been wanting to start, but perhaps don’t have the revenue to start it,” he said.

“I’m hoping that when people engage in traditional healing services, a lot of it is to bring balance back into the lifestyle, to give them some hope,” Molina said.

That’s the effect traditional healing practices have had on Harrison Jim, who is Diné. Now a counselor and traditional practitioner at Sage Memorial Hospital in Arizona, Jim, 70, said he remembers his own first all-night sweat lodge ceremony when he returned from a military tour.

“I [felt] relieved of everything that I was carrying, because it’s kind of like a personal journey that I went through,” he said. “Through that ceremony, I had that experience of freedom.”

Kim Russell, the hospital’s policy adviser, who also spoke on the panel about the traditional healing waivers, told Stateline her team hopes to bring on another practitioner along with Jim.

Tribal health leaders have expressed concern about people without traditional knowledge posing to offer healing services. But Navajo organizations, including Diné Hataałii Association Inc., aim to protect from such co-opting as it provides licensures for Native healers, Jim said.

Push in Washington

Facilities covered under the new waivers include Indian Health Service facilities, tribal facilities, or urban Indian organization facilities. In Arizona, urban Indian organizations can get the benefit only if they contract with an Indian Health Service or other tribal health facility.

In Oregon, Yellowhawk Tribal Health Center spokesperson Shanna Hamilton said that while the center can’t speak on behalf of other tribes or clinics, many are still in the early stages of developing programs and protocols. She called the waivers a “meaningful step forward in honoring Indigenous knowledge and healing practices.”

Meanwhile, in neighboring Washington state, a bill that would have required the state to submit an application for a waiver by Sept. 1 died in committee.

But the state doesn’t need the legislative OK to apply. It’s still going to submit an application by the end of the year, the Washington State Health Care Authority told Stateline in a statement, emphasizing that each tribe would determine its own traditional health services available for reimbursement.

Azure Bouré, traditional food and medicine program coordinator for the Suquamish Tribe, a community along the shores of Washington’s Puget Sound, called the waivers “groundbreaking.”

“We’re proving day in and day out that Indigenous knowledge is important. It’s real, it’s worthy, and it’s real science,” Bouré said.

On a brisk summer day in 2009, Bouré recalled, she had attended a family camp hosted by Northwest Indian College. It was then she tasted the salal berry for the first time. A sweet, dark blue berry, it’s long been used by Pacific Northwest tribes medicinally, in jams, and for dyeing clothing.

“It was just that one berry, that one day, that reignited that wonderment,” Bouré said. For her, it unlocked the world of Indigenous plant medicine and food sovereignty, a people’s right to the food and food systems of their land.

She got her bachelor’s in Native American environmental science and now runs an apothecary, teaches traditional cooking classes, recommends herbs to members with ailments and processes foraged foods.

One day she could be chopping pumpkins or other gourds and the next, cleaning and peeling away the salty-sweet meat from dozens of sea cucumbers harvested by shellfish biologist divers employed by the tribe.

Bouré’s grandmother died when her mom was 12 years old. “That’s a whole generation of knowledge that she lost,” she said. One way she unearths that lost knowledge is by learning tribal medicine and teaching it, and holding on to memories like watching her great-grandmother Cecelia, who wove traditional sweetgrass dolls even when she was blind.

“I think that I come from a long line of healers,” she said. “It just skipped my mom and my grandma that passed, but I really relate to my great-grandmother Cecelia in that way.”

Dr. Gary Ferguson, who is Unangax̂ (Aleut), is the director of integrative medicine at the Tulalip Health Clinic about 40 miles north of Seattle. He’s certified in naturopathic medicine in Washington and Alaska.

His health center already has a variety of integrative medicine offerings, he said, including traditional ones grounded in Coast Salish traditions of the Pacific Northwest. He said he hopes the waivers and continued support for Indigenous ways of healing will help tribes address health disparities.

“These ceremonies and ways are part of that deeper healing,” he said.