Picture a wildfire raging across a forested mountainside. The smoke billows and the flames rise. An aircraft drops vibrant red flame retardant. It’s a dramatic, often dangerous scene. But the threat to water supplies is only just beginning.

After the smoke clears, the soil, which was once nestled beneath a canopy of trees and a spongy layer of leaves, is now exposed. Often, that soil is charred and sterile, with the heat making the ground almost water-repellent, like a freshly waxed car.

When the first rain arrives, the water rushes downhill. It carries with it a slurry of ash, soil and contaminants from the burned landscape. This torrent flows directly into streams and then rivers that provide drinking water for communities downstream.

As a new research paper my colleagues and I just published shows, this isn’t a short-term problem. The ghost of the fire can haunt these waterways for years.

This matters because forested watersheds are the primary water source for nearly two-thirds of municipalities in the United States. As wildfires in the western U.S. become larger and more frequent, the long-term security and safety of water supplies for downstream communities is increasingly at risk.

Charting the long tail of wildfire pollution

Scientists have long known that wildfires can affect water quality, but two key questions remained: Exactly how bad is the impact? And how long does it last?

To find out, my colleagues and I led a study, coordinated by engineer Carli Brucker. We undertook one of the most extensive analyses of post-wildfire water quality to date. The results were published June 23, 2025, in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

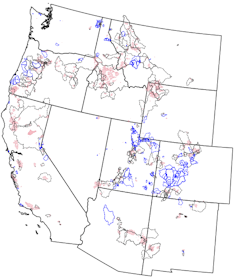

We gathered decades of water quality data from 245 burned watersheds across the western U.S. and compared them to nearly 300 similar, unburned watersheds.

By creating a computer model for each basin that accounted for its normal water quality variability, based on factors such as rainfall and temperature, we were able to isolate the impact of the wildfire. This allowed us to see how much the water quality deviated after the fire, year after year.

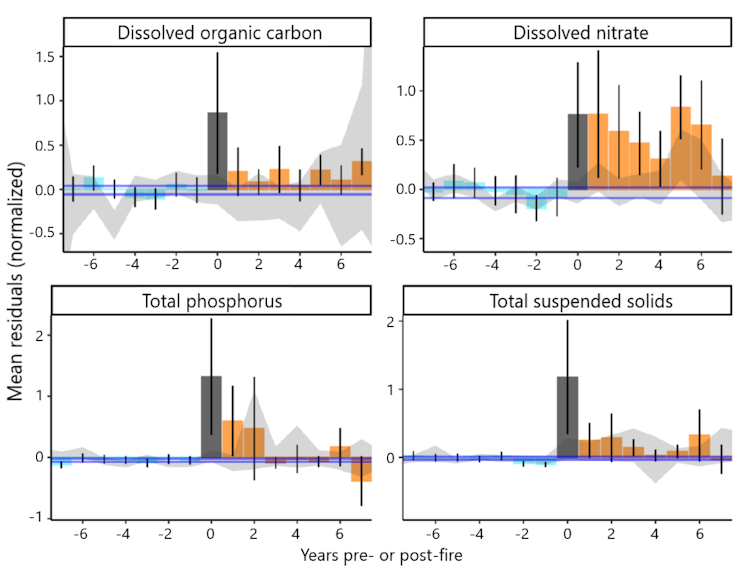

The results were stark. In the first year after a fire, the concentrations of some contaminants skyrocketed. We found that levels of sediment and turbidity – the cloudiness of the water – were 19 to 286 times higher than prefire levels. That much sediment can clog filters at water treatment plants and require expensive treatment and maintenance. Think of trying to use a coffee filter with muddy water – the water just won’t flow through.

Concentrations of organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus were three to 103 times greater in the burned basins. These dissolved remnants of burned plants and soil are particularly problematic. When they mix with the chlorine used to disinfect drinking water, they can form harmful chemicals called disinfection byproducts, some of which are linked to cancer.

More surprisingly, we found the impacts to be really persistent. While the most dramatic spikes in phosphorous, nitrate, organic carbon and sediment generally occurred in the first one to three years, some contaminants lingered for much longer.

We saw significantly elevated levels of nitrogen and sediment for up to eight years following a fire. Nitrogen and phosphorus act like fertilizer for algae. A surge of these nutrients can trigger algal blooms in reservoirs, which can produce toxins and create foul odors.

This extended timeline suggests that wildfires are fundamentally altering the landscape in ways that take a long time to heal. In our previous laboratory-based research, including a 2024 study, we simulated this process by burning soil and vegetation and then running water over them.

The stuff that leaches out is a cocktail of carbon, nutrients and other compounds that can exacerbate flood risks and degrade water quality in ways that require more expensive treatment at water treatment facilities. In extreme cases, the water quality may be so poor that communities can’t withdraw river water at all, and that can create water shortages.

After the Buffalo Creek Fire in 1996 and then the Hayman Fire in 2002, Denver’s water utility spent more than US$27 million over several years to treat the water, remove more than 1 million cubic yards of sediment and debris from a reservoir, and fix infrastructure. State Forest Service crews planted thousands of trees to help restore the surrounding forest’s water filtering capabilities.

A growing challenge for water treatment

This long-lasting impact poses a major challenge for water treatment plants that make river water safe to drink. Our study highlights that utilities can’t just plan for a few bad months after a fire. They need to be prepared for potentially eight or more years of degraded water quality.

We also found that where a fire burns matters. Watersheds with thicker forests or more urban areas that burned tended to have even worse water quality after a fire.

Since many municipalities draw water from more than one source, understanding which watersheds are likely to have the largest water quality problems after fires can help communities locate the most vulnerable parts of their water supply systems.

As temperatures rise and more people move into wildland areas in the American West, the risk of wildfires increases, and it is becoming clear that preparing for longer-term consequences is crucial. The health of forests and our communities’ drinking water are inseparably linked, with wildfires casting a shadow that lasts long after the smoke clears.![]()

Ben Livneh, Associate Professor of Hydrology, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.