Secret societies and masquerade fever took over Colorado’s social scene in the 1870s

© ogichobanov - iStock-1088402018

Though it wouldn’t be formally established as a federal holiday until 1879, Washington’s Birthday — later Presidents’ Day — was celebrated with special enthusiasm across the country in the centennial year, and Colorado was no exception.

All around the territory, businesses were closed, with residents turning out for parades, military salutes and a variety of “out-door games and literary exercises,” reported the Denver Tribune. In the evening, grand balls were held in Golden at Standly’s Hall, in Boulder at Union Hall and in Georgetown at Cushman’s Opera House.

© Evgeniy Grishchenko - iStock-2155580431

In Las Animas, a newly organized Masonic lodge hosted guests from nearby Fort Lyon and towns as far away as Granada and Kit Carson, who took to the freshly waxed and polished dance floor as an orchestra played waltzes and quadrilles until 3:30 a.m.

The Las Animas Leader could hardly have been more effusive about the event’s success. Not only was it “doubtless the most brilliant gathering of all which have so far taken place in this part of the territory,” the Leader wrote, the holiday ball had demonstrated that “this community possesses and presents in its social circle a standard of refinement and intelligence which would be creditable anywhere in the country.”

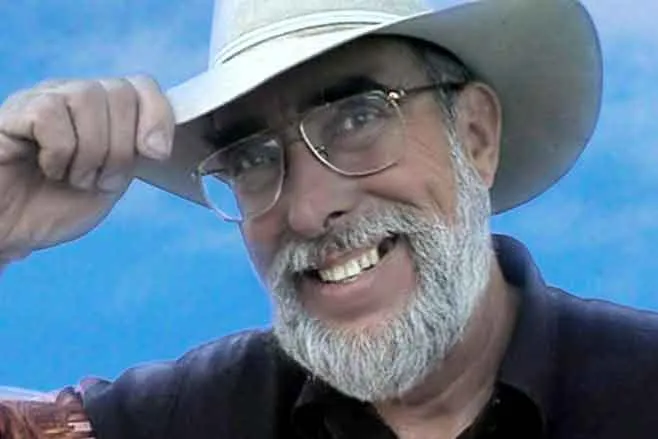

As was the case in fledgling settlements all over Colorado, the Leader’s local boosterism overlapped with self-interest: The small weekly paper’s owner and publisher, Charles Bowman, was a member of the ball’s organizing committee, and a prominent Mason.

Colorado’s early decades as a territory and state coincided with the so-called Golden Age of Fraternalism, when millions of American men joined societies like the Freemasons, the Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythia and many more. In 1876, there were five separate Masonic lodges in Denver alone, along with dozens of other social clubs, military orders and benevolent societies formed by the city’s various immigrant and religious communities.

Aside from business connections and a sense of belonging, these groups offered their members an early social safety net in the form of mutual aid and insurance benefits. Especially in the fast-growing cities and towns of the West, fraternal orders and the gathering places they built served important social and civic functions. Colorado’s final territorial Legislature was held in 1876 on the first floor of Denver’s newly opened Odd Fellows Hall — at the same time its constitutional convention met in the space the order had just vacated.

The Maennerchor masquerade

In Denver, the holiday’s main event during daylight hours was a trap shooting match put on by the Denver Shooting Club, which arranged for horse-drawn streetcars to ferry spectators to its club grounds at 26th and Glenarm streets. At the time, though a growing number of people considered the practice cruel, the targets shot in such events were not clay decoys but live pigeons. Longtime Denver gunsmith Carlos Gove took the top prize, though the Denver Times noted that due to a “lack of pigeons,” ties for third and fourth place would have to be “shot off in a few days.”

iStock

In the evening, Jack Langrishe, the famous frontier impresario whose acting troupe had arrived for its latest stint in Denver earlier in the month, staged a double feature of comedies, “The Serious Family” and “Poor Pillicoddy,” at the Denver Theater.

But the “grandest success of the season,” in the Denver Times’ judgment, took place at Guard’s Hall, where the Maennerchor, the city’s German-American singing social club, hosted hundreds of masked and costumed guests for a Centennial Carnival.

Masquerades, a favorite pastime of Europe’s elite since the 15th century, rose in popularity among the ascendant American aristocrats of the Gilded Age, peaking with the famously lavish Vanderbilt Ball held in New York City in 1883.

“What fun it is to see masks squeezing each other in a fancied intrigue when, perhaps, they are neighbors, see each other three times a day, and feel, in ordinary life, the most comfortable indifference for each other,” said the Rocky Mountain News.

Preparations for the Maennerchor masquerade had been carried on for weeks, with Mrs. Candace Bement and Madame Eugenie Putz, dressmakers on Larimer Street, competing for the brisk trade in domino masks, wigs, hats and other costume pieces. In commemoration of the Centennial, masqueraders dressed up as figures like George and Martha Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, British and Continental soldiers and more.

“These annual balls of the Maennerchor … take the lead of all our masquerades, in the extravagance of grotesquerie,” said the News. “No previous ball approached this one, it is claimed, in the number of spectators present, the participants in the festivities, or in the variety of characters, ranging all the way from the cheapest to the costliest costumes.”

Conflict in the Black Hills

The News’ extensive Feb. 24 account of the decadent Maennerchor ball and its costumed soldiers was immediately followed in its columns by an early report of the trouble brewing a few hundred miles north of Denver.

A Wyoming correspondent wrote of the “suddenly organized expedition” of Gen. George Crook, who was preparing to march out of Fort Fetterman in a winter campaign against the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne in the Dakota Territory. Crook’s maneuvers began the Great Sioux War of 1876, a yearlong conflict that would culminate in one of the most famous defeats in U.S. military history and cast a pall over the Centennial celebrations later that summer.

Over the preceding two years, thousands of gold prospectors had flocked to the Black Hills, trespassing on land considered sacred by the Lakota and other tribes and reserved for them under the terms of an 1868 treaty.

Federal officials sought to force the tribes to negotiate the region’s sale — they’d similarly pressured the Ute people into a cession of Colorado’s silver-rich San Juan Mountains — but Lakota leaders Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse refused. Tensions reached a breaking point as prospectors and settlers, many of them relocating from the Colorado Territory, continued to flood in at the gold rush’s peak in early 1876.

“FOR SALE — CHEAP — SALOON … going to Black Hills,” read a Feb. 22 classified ad in the News.

The troops under Crook would march north against the Lakota and Cheyenne in March and again in May — when they would be joined by a cavalry force marching west from Fort Abraham Lincoln under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, a Civil War veteran whose 1874 expedition into the Black Hills had kicked off the gold rush.

Selected sources

- The Rocky Mountain News (Daily), Feb. 22 & 24, 1876

- The Denver Tribune, Feb. 22, 1876

- Las Animas Leader, Feb. 25, 1876

- White, Richard. “The Republic For Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896”